|

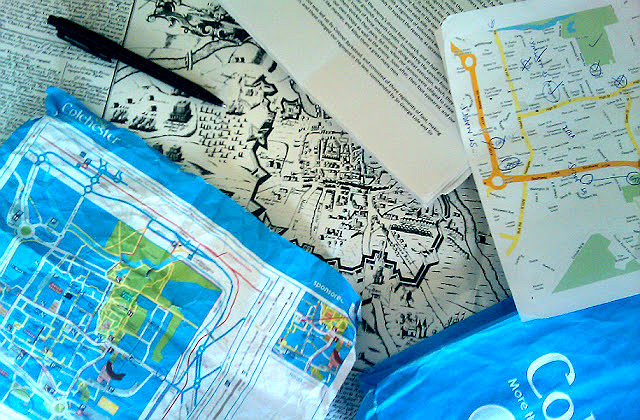

| Old and new maps of Colchester |

The Hoydens are delighted to welcome Struan Bates of The English Civil War website. If you are interested in the English Civil War his site is well worth a visit and he has recently set up a forum for those of us passionate about the English Civil War.

A couple of weekends back I managed a quick jaunt around the surviving sites from the 1648 Siege of Colchester.

My guides: the excellent 1997 reprinting of a contemporary siege map produced by Colchester Archaeological Society and the detailed account transcribed in Daniel Defoe's 1722 Essex tour diary ...

The town was subjected to 11 weeks of bombardment by Fairfax after a combined Royalist force retreated into the town on the 12th June. Broadly in support of Parliament since the outbreak of war, Colchester was in little mood to provide a base for a resurgent Royalist army in the south-east looking to win a 'second' English Civil War.

After failing to take the town quickly by storm, Fairfax surrounded the walled town with his own siege works. Like most towns and cities subject to prolonged artillery fire, many buildings were severely damaged or lost outright.

|

| The bridge of the River Colne on the east road out of the town. Siege House can be seen to the rear. |

Early fighting saw the eastern bridge over the Colne contested. The mill (located on the same site as the newer building, seen above), was taken by the Parliamentarians on the 5th July. Sallies by the besieged forces caused damage to the red and black timbered building (Siege House) to the far right.

|

| The Siege House Restaurant, an early 16th century timber construction. |

Now a restaurant called the 'Siege House', the jetted first floor has musket ball holes embedded into its west side - probably caused by the sallying Cavaliers as they sought to push back the attackers up the Suffolk Road. More holes pepper the south front, facing the road.

|

| Musket ball holes marked on the west side of Siege House. |

The Royalist forces inside the walls comprised a number armies seeking to re-ignite support for the King in the south-east. Lord Norwich, Lord Capel, Lord Loughborough and Sir George Lisle had been driven by Fairfax from Kent, fighting up through Essex through Chelmsford and finally to Colchester.

Here they joined Sir Charles Lucas, commander of the Essex forces and owner of Lucas House - a mansion in the grounds of St John's, a 11th century Benedictine abbey to the south of the walls.

|

| St John's Abbey Gateway, the only surviving part of an 11th century Benedictine abbey. |

Fairfax - joined by Thomas Honywood and John Barkstead - had by now 5000 men at his disposal. His artillery destroyed most of the abbey and Lucas House, with only the gateway (above) surviving.

Almost due north from here, and just metres from the the southern town wall, was St Botolph's Priory. The former Augustinian priory had passed to secular owners during the Dissolution, though the church remained in use.

|

| St Botolph's fell early due to its location outside of the town walls. |

St Botolph's suffered heavily. By the 20th July it had already been partly demolished, with a battery set up adjacent to pound the southern wall.

|

| The damage to St Botolph's caused by Fairfax's artillery was never repaired. |

Originally around 3000 yards long at their perimeter, the walls were built c.65-80 AD. Strengthened by the addition of strategically placed forts at the outbreak of war in 1642, they were hastily re-fortified by the Cavaliers once they had taken refuge inside.

|

| The longest stretch of the wall lies to the south, boarding the Priory Street car park. The photo shows a section repaired after the siege. |

On the same day that Lucas's house was taken, a battery was set up near it at St John's green to bombard the church of St Mary-at-the-Walls, where an elevated Royalist artillery position threatened forces approaching from the west.

|

| A damaged part of the wall with St Mary-at-the-Walls in the background. |

The photo above shows the partly demolished western wall, with the church on the ridge behind.

|

| St Mary-at-the-Walls. The lower part of the original tower (left) remains. |

The Roundhead guns shot the top of the Norman tower. The original lower part of the tower remains, with the redbrick re-building taking place in the early 18th century.

A number of attempts by Royalist units to flee the town were prevented. As the siege progressed, fear of starvation began to drive the garrison to desperate lengths.

On the 22nd June they began to slaughter horses for food.

|

| The stunted tower of St Martin's, unrepaired after the siege. |

St Martins, further towards the centre of the town, also took significant damaged. The 12th century tower was decapitated, leaving the squat building standing today.

Even by 17th century standards the siege was turning pretty grim. The start of August saw the townspeople protesting by the city gates at the terrible conditions, demanding to be fed or allowed to leave. The Parliamentarian troops outside ignored their pleas on Fairfax's orders, despite the town's loyalty during the 'first' Civil War, and atrocities were being reported by both sides.

On the 7th August it was recorded that Colchester's inhabitants had taken to eating cats, dogs, soap and candles to stay alive.

|

| Colchester Castle |

Word came on the 22nd August that Cromwell had defeated the Scots Engager army at Preston. The celebrating Roundheads flew kites over the town wall in the hope that - with no possibility of being relieved by friendly forces from the north - the Cavaliers would finally surrender.

This they did on the 27th August, on Fairfax's terms. All Lords and Gentlemen were to be taken prisoner, with common soldiers sent home on condition that they never again take up arms against Parliament.

The Royalist aristocrats were to be tried by Parliament. Capel was sent to the Tower (eventually executed the following year), while Norwich and Loughborough were exiled.

Lucas and Lisle were found guilty of High Treason by court-martial. They were sentenced to death on several grounds, one of them being that their refusal to surrender had delayed the siege, thereby causing further unnecessary loss of life.

|

| A monument to the rear commemorating the exact place where Lucas and Lisle were shot. |

The men were led out to a spot around the back of the castle. Lucas faced the firing squad first, opened his shirt and inviting the "rebels" to "do their worst" before the shots rang out.

Lisle walked forward and kissed his dead friend before inviting the firing squad to stand closer. The commanding officer assured Lisle that they would certainly hit him, to which Lisle replied “I have been nearer to you, friend, when you missed me”. He matched Lucas's brave example by opening his shirt and asking them once more to "do their worst".

|

| Legend had it that for grass never grew on the spot where the two commanders were killed. |

The small obelisk marking the place of execution today attributes the order to execute the men to Fairfax alone, however evidence appears unclear whether this was the case or whether Henry Ireton had a significant hand in the decision.

Fairfax had captured Colchester, but the 'murders' of the two prominent commanders caused outrage, and quickly elevated them to Royalist martyrs.

A smaller copy of the siege map at British History Online

http://colchesterhistoricbuildingsforum.org.uk