Ay, but to die, and go we know not where;

To lie in cold obstruction and to rot;

This sensible warm motion to become

A kneaded clod; and the delighted spirit

To bathe in fiery floods, or to reside

In thrilling region of thick-ribbed ice;

To be imprison’d in the viewless winds,

And blown with restless violence round about

The pendent world.

Shakespeare, Measure for Measure 1604

In the seventeenth century evidence of mortality was present everywhere and often the causes of death were little understood. London preacher Sampson Price wrote, 'Some we see come to their graves by apoplexies, lethargies,dead palsies, some by sudden blows, some as a wasted candle goes out naturally.' Death was altogether mysterious. In the 17th century the death rate was 25-35 per 1000 of the population (currently in the modern west it is at 8 per 1000), and as many as a quarter of women who died, died in childbirth. (Source - David Cressy)

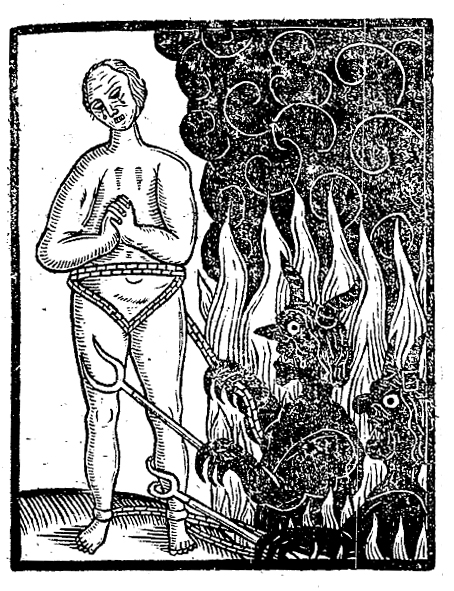

The prevailing view at this time was that death was a consequence of man's sin 'begot of the devil' (James Cole) and so death was personified as an adversary or tyrant, whose sole aim was to destroy unwary sinners. Often death was drawn as a walking skeleton with a scythe, arrow, or spade in hand to dig the grave.

|

| Fall of the Rebel Angels Rubens 1620 |

Catholics and Protestants had two different views of the afterlife. Protestants had rejected the idea of purgatory in 1574, believing it to have no scriptural foundation.

'the soul after death...does not wander up and down from place to place, nor yet remaineth in a third place, as papists and pagans have dreamed' Clergyman Robert Pricke 1608

So now there were only two possibilities - salvation or damnation.

This was a change which was enormously significant as it affected the entire view of the relationship with deceased family members. Suddenly there was no point to to masses, dirges or prayers for the dead, and the removal of this comfort had a profound effect on mourning and funeral custom. The deceased was no longer affected by any sort of intercession, so immediately conduct here on earth became crucial, and as everyone trasgresses as least in some way, the fear of hell became even more pronounced.

'For truth I may this sentence tell, No man dies ill that liveth well.' Poet Robert Herrick

From a Broadside Ballad - St Bernard's Vision of Hell (1640)Most wretched Flesh, which in thy time of life

Wast foolish, idle, vain, and full of strife;

Though of my substance thou didst speak to me,

I do confess I should have bridled thee.

But thou through love of pleasure foul and ill,

Still me resisted and would have thy will:

When I would thee (O Body) have control’d,

Straight the worlds vanities did thee with-hold.

So thou of me didst get the upper hand,

Enthralling me in worldly pleasures band,

That thou and I eternal shall be drown’d

In Hell, when glorious Saints in Heaven are crown’d.

So though the bodies of protestant souls remained in the churchyard, their souls were now beyond help and had either gone immediately to their reward, or were already in eternal torment in the gates of hell. Although the removal of purgatory from the view of the population was supposed to be the law - for example Bishop Richard Barnes of Durham instructed his parish that, 'no communions or comemmorations be said for the dead...nor any superfluous ringing at burials' - in practice very few were willing to give up their familiar practices. 'Prayers for the dead' was such an ingrained social custom that it took almost a century for it to draw to a close.

Those who chose to maintain the Catholic faith - recusants - held their funerals at unlikely hours, or performed them quietly at home. But it was not only recusants who fell foul of the law: At Ribchester in 1639 one Robert Abbott was charged with an offence in which 'there was a cross towel laid over her corpse upon the bier, and she was set down at stone and wooden crosses by the way; and you did at the same cross in a superstitious manner take off your hat and kneeled down and prayed.'

In Stuart times these offences were as likely to be committed by protestants who felt unable to let go of the idea of purgatory. Unsurprisingly most people held a 'belt and braces' attitude. If there was even a faint possibility that prayers could do their dead relative good, then they would use them, and traditions such as praying for the soul on the route to burial, or putting a penny in the mouth of the deceased for him to pay St Peter, still lingered right up to the end of the 17th century.

Both Catholics and Protestants continued to believe that there would be a general resurrection for the just, at the time of Christ's second coming, so the separation caused by death was only temporary. Whether this 'resurrection' was bodily and material, or metaphorical, was a matter for debate - just as it is today.

|

| Resurrection of the Flesh by Luca Signorelli |