The City skyline was characterised by the spires of innumerable churches from all the different parishes : St Giles, Criplegate, St Mary le Bow, (of the famous Bow Bells) St Michael Paternoster. Most had been there since medieval times, and all had bells to summon parishioners to prayer, to ring out for births, marriages and deaths, and to tell the hour. More about these churches can be discovered in Reaching for the Heavens: the City Churches of Medieval London by Sarah Valente Kettler & Carole Trimble.

Just what this skyline looked like can be seen in Visscher's fabulous engraving, a map I consulted often whilst working out the layout of London for all three of my novels. Of course the landscape is dominated by the bridge (see my previous post) - still the only one across the Thames, and St Paul's Cathedral, which undfortunately had lost its spire during a storm when it was struck by lightning.

Southern Bridge Gate still held the spikes which displayed the heads of traitors. In my novel these traitors would likely have been the Gunpowder Plotters, to act as a warning to Catholics about their fate should they decide to try the same ploy to remove James I from the throne.

Living in the city was not as romantic as it looks from a distance as narrow alleyways led down to the river where the night-soil men dumped the city's waste. Within the actual city streets the houses were two to three storeys high, with overhangs that blocked the light. Apart from churches, the other large buildings were the Halls of the City Companies, such as Brewers, Bankers, Cloth Merchants. London trade through shipping made up a third of all England's trade. The Halls had often been acquired from the monasteries after the dissolution (in fact in The Gilded Lily, Whitgift's Pawnbrokers is on just such a site.)

|

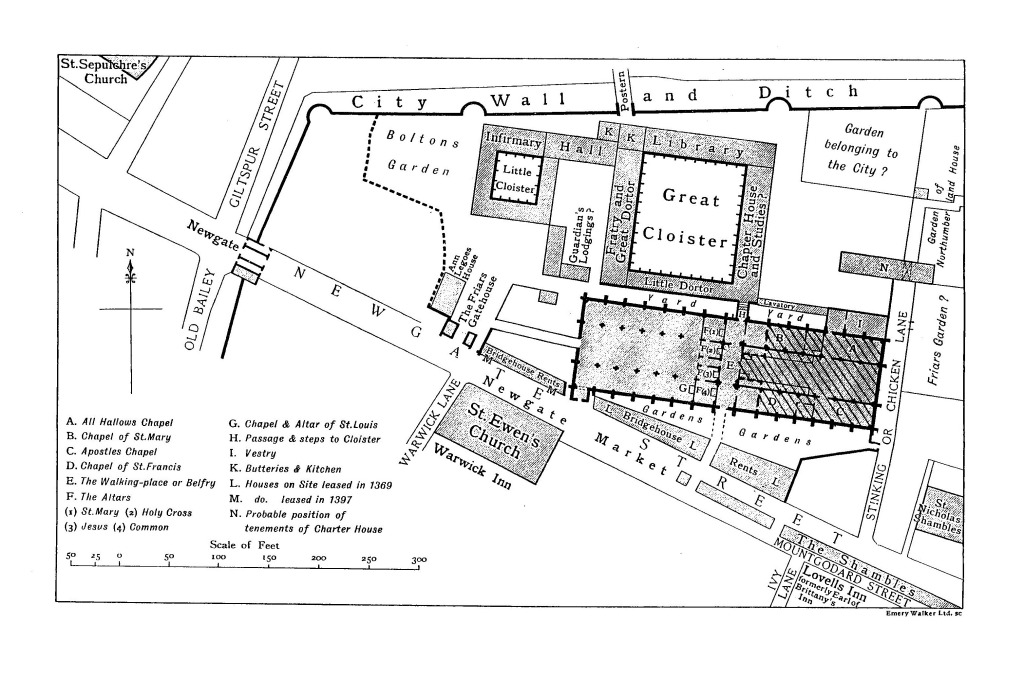

| Plan of Greyfriars Monastery before it was used as a hospital |

Another example of a monastery being re-used is the old cloisters of Greyfriars Monastery in Newgate Street, which became a hospital for poor children, known as Christ's Hospital. As well as housing the invalid poor, the former nave was used by a stationer to store books. You can imagine how the repressed Catholics felt, seeing their holy buildings now converted for trade - and not always ethical trade at that.

There was some new building going on at this time though, but upstream at Westminster, then unconnected to the city itself. Nearing completion was the new Banqueting Hall by Inigo Jones. It was built to replace a previous one lost by fire, and linked to the city via a highway running through the village of Charing. It was set amongst other noblemen's houses which enjoyed the setting of formal gardens. The purpose of this building in 1622 was to act as a symbol to glorify the house of Stuart, and provide the centrepiece of a proposed palace. The actual banqueting hall is just a fraction of the development below, shown just to the left of the main courtyard, so you can see how ambitious the plans were.

Outside the city gates though, the houses sprawled haphazardly beyond the walls. The population increased from 250,000 to 400,000 from the beginning of James's reign until the Great Fire. This is even despite the Plague which killed 100,000 people. Slum areas within the city and outside its walls became gradually known as 'rookeries'. One famous rookery is the St Giles area and it existed from the 17th century and into Victorian times. Another is Seven Dials - named for its innovative plan of seven streets radiating from a central 'sundial'. Unfortunately Seven Dials became overrun with cheap and shoddy housing and soon became a byword for the hangout of the criminal underclass. More about rookeries in The Beer Flood - the tale of the exploding brewery in St Giles.

|

| Rookery at St Giles about 1800 |

|

| Bampfylde House Exeter |

You can find out more about Jacobean Houses and Bampfylde House in particular on another of my posts here. Scroll down to find the post. Happy Reading!

My latest book - A Divided Inheritance - is the story of a lace-trader's daughter who must leave her London home to track down her cousin, a man who has stolen her inheritance.

Not only must she confront the cousin she loathes, but she must travel to Seville, a city in the grip of the Inquistion, and a place which in 1610 is about to undergo one of the biggest upheavals in its history.

More about my researches about Golden Age Seville and the book can be found on my website

Bibliography : Wren's London by Eric de Mare

The Illustrated Pepys by Robert Latham

Life in Stuart London by Peggy Miller