In 1688, King James II fled to France, leaving the throne of England open to a bloodless coup by his nephew and son-in-law, the Calvinist William of Orange. Many Highland clans had openly sworn their allegiance to their deposed

‘King Across the water’ and John Graham of Claverhouse, ‘Bonnie Dundee’ led an uprising in 1689 to restore the Stuart King. It failed, leaving Dundee dead and many Highlanders dispossessed and impoverished.

In August, 1691, King William III offered a pardon to the Highland clans if they took an oath of allegiance, after which the chiefs would be restored to their estates. By the end of 1691, the terms had become threatening - the clans would sign the agreement by 1st January 1692, or be punished with the

'utmost extremity of the law'.

The MacDonalds had lived in the Glencoe pass since the early 14th Century, when they supported King Robert the Bruce. From Loch Leven at its northern end to Rannoch Moor in the south, the pass is flanked by rugged mountain scenery that suffers frequent arctic winters.

|

| James Dalrymple Earl of Stair |

Alastair MacDonald, 12th Chief of Glencoe, known as MacIain, had joined Claverhouse in 1689. A huge man with flowing white hair, beard and moustache, well respected by his own clan, and feared by others. The MacIains were Reivers, famous for their raiding, pillaging and cattle rustling, and their main enemy was the neighbouring Campbell clan. After two successive Earls of Argyll had been executed and the Campbells weakened, the MacDonalds pillaged huge tracts of Campbell territory in the Atholl Raid of 1685.

Before they could take the oath of allegiance to King William, the Highland clans sent Ambassadors to France to obtain a release from their oath to King James II; a release that was granted on December 12th 1691, though the messenger bringing it didn’t arrive in the Highlands until December 28th - leaving only three days until the deadline.

During the worst of a Highland winter, MacIain left for the newly-built Fort William and presented himself to its Governor, Colonel John Hill, an experienced English officer who had fought with Cromwell. Hill told MacIain that only the civil magistrate could administer the oath, so armed with a letter for Sir Colin Campbell, the sheriff of Argyllshire, MacIain, a man of sixty-one, had to walk the 74 mile journey in deep snow to Inverary, the stronghold of the Campbell clan.

MacIain didn’t even stop to tell his family what was happening, though he passed within half a mile of his own house. He negotiated the Barcaldine Estate, where he was captured by Grenadiers, although only detained for a day, when he reached Inverary on 2nd January to discover that Sheriff Sir Colin Campbell had not yet returned from the New Year festivities, so MacIain had to cool his heels for another three days.

Sir Colin declined at first, by MacIain importuned him with tears and then threatened to protest. On the 6th of January 1692, Sir Colin administered the oath, assuring MacIain's allegiance would be accepted, sent a certificate of compliance to Edinburgh and a letter to Campbell at Fort Willliam that said:

|

| Painting by James Hamilton |

"I endeavoured to receive the great lost sheep, Glencoe, and he has undertaken to bring in all his friends and followers as the Privy Council shall order. I am sending to Edinburgh that Glencoe, though he was mistaken in coming to you to take the oath of allegiance, might yet be welcome. Take care that he and his followers do not suffer till the King and Council's pleasure be known."

In Edinburgh, Sheriff-Clerk Campbell, Secretary of State for Scotland, John Dalrymple, Master of Stair, and several Privy Councillors, were shown the certificate with MacIain’s signature and Hill’s letter, but instead of presenting MacIain's case, the Sherriff-Clerk Campbell scored MacIain’s name off the certificate. Thus Dalrymple, a Lowlander and Protestant who disliked Highlanders and especially the MacIain, saw this as his opportunity to destroy the MacDonalds and despatched a document to Sir Thomas Livingston, the Commander-in-Chief of the King's forces in Scotland:

"You are hereby ordered and authorised to march our troops which are now posted at Inverlochy and Inverness and to act against these Highland rebels who have not taken the benefit of our indemnity, by fire and sword and all manner of hostility; to burn their houses, seize or destroy their goods or cattle, plenishings or clothes, and to cut off the men."

-these orders were accompanied by Dalrymple's letter which reads,

"Only just now, my Lord Argyle tells me that MacDonald of Glencoe has not taken the oath, at which I rejoice. It is a great work of charity to be exact in rooting out that damnable sept, the worst of the Highlands."

Three commanders - two from the Campbell-dominated Argyll regiment and one from Fort William were ordered to Glen Coe by the beginning of February to await further orders. On approaching the Glen, they were met by John MacDonald, the elder son of the chief, at the head of about 20 men, who demanded Campbell’s reason for coming into a peaceful country with a military force; Glenlyon and two subalterns declared they came as friends, their sole object being to collect the arrears of cess and hearth-money, - a new tax laid on by the Scottish parliament in 1690. Lieutenant Lindsay produced the instructions signed by a now deeply troubled Colonel Hill, the Governor of Fort William.

Captain Robert Campbell of Glenlyon, who was possibly chosen because his niece, Sarah was married to MacIain's younger son, Alexander, [Sandy MacDonald], was put in charge of not only of his own company of infantrymen but the grenadiers, whose commander was Captain Thomas Drummond, the same man whom MacIain had encountered on his way to take the oath of allegiance; a man who would be absent until the eve of the attack.

Using the excuse the fort was full, Glenlyon arrived at Glencoe on 1 February 1692 and claimed hospitality from the MacDonalds. His men were quartered in the clan’s own houses, where they stayed for the next twelve days with Glenlyon making regular visits to Sarah, the sister of Rob Roy MacGregor, and young Sandy MacDonald for the traditional, ‘morning drink’.

On Friday evening, 12th February, Glenlyon played cards with Sandy and his brother John MacDonald, having also accepted an invitation from MacIain to dine with him the following day.That night, a blizzard howled through Glencoe, giving whiteout conditions and just before dawn, John MacDonald, the chief’s eldest son, was woken by voices outside his house. He dressed and went to Glenlyon's quarters at Inveriggan, where the whole detachment was preparing for action. John demanded an explanation, and was told by Glenlyon that the troops had orders to march against some of Glengarry's men and assured him they had no hostile intent toward the MacDonalds. John accepted this reasoning, after all, hadn’t they all

played cards together the night before, and wouldn’t Glenlyon have warned his niece and Sandy MacDonald?

Reassured, John returned home, but couldn't settle, and when an equally anxious servant told him that twenty troops approached the house with fixed bayonets on their muskets, John gave instructions to waken his brother, Sandy, and then fled to the hills. When soldiers burst through the door moments later, the house was empty – Sandy and his family had also escaped, their tracks covered by the blizzard. High in the hill above the village of Auchnaion, shots were heard by John, Sandy MacDonald, and their families.

At Inveriggan, Glenlyon had ordered that nine men who had been held, bound and gagged for the past few hours be taken outside and shot. MacDonald of Inveriggan, Glenlyon's host for the past fortnight, and a man with a letter of protection signed by Colonel Hill was one of these.

At MacIain’s house in Carnoch, Glenlyon's junior officer, Lieutenant Lindsay, arrived with a party of soldiers and apologised to a servant for calling so early; thus MacIain's murderers were invited into the house. Glencoe was shot twice as he was getting out of bed and fell lifeless in front of his wife, who was stripped naked and thrown out of the house. One of the soldiers is said to have pulled the rings from her fingers with his teeth, then she was left in the snow and died the following day.

At the laird's house in Auchnaion, where Sergeant Barber had been quartered, ordered a detail to attack. Five men were killed instantly and another three wounded. Amongst those injured was MacDonald of Auchintriaten, who also had a letter of protection signed by Colonel Hill. As he was about to be finished off by Barber, he asked if he was to be murdered beneath the roof that they had shared for the past fortnight. Barber agreed to kill him outside and ordered two soldiers to escort him. Once through the door, MacDonald threw his plaid over their faces and fled, surviving to recount the story.

Men were dragged from their beds and murdered, their houses torched, while women of all ages, some almost in a state of undress, the old and the frail, mothers carrying infants and some with young children climbed up the mountains in the blizzard, many to be overcome by exhaustion and die of exposure before they reached shelter.

Lieutenant-colonel Hamilton and his men, delayed by the blizzard, did not reach Glencoe until six hours after the main attack. By this time the MacDonalds were dead or fled, so they had nothing to do but set fire to the houses, collect the cattle and anything valuable in the Glen, which they took to Inverlochy and divided among the officers of the garrison. One man of seventy who remained in the glen, was put to death on Hamilton’s orders.

When the sun rose the next morning, thirty nine men, women and children lay dead, though MacIain’s two sons escaped, possibly helped by the late arrival of an additional force of redcoats due to a blizzard, who should have blocked the entrance to the glen.

Enigma

As a surprise attack three hours before dawn, why did it begin with gunfire and not swords and daggers? The Argyll regiment consisted of 135 soldiers, only a dozen of whom were Campbells, but of two hundred McDonalds in Glencoe that night, only thirty eight deaths occurred. It seems almost certain that some of the Campbell soldiers, disgusted with their orders, alerted the families who had been their hosts, giving them time to escape and at least wrap up against the blizzard.

Two of Glenlyon’s lieutenants refused to carry out the murders and broke their swords –

[Prebble suggests that they were Francis Farquhar and Gilbert Kennedy] both were later prosecuted but freed. Government soldiers were sent to block off the passes out of the Glen, including the Devil's Staircase from Kinlochleven, but fleeing McDonalds were more likely to go the other way towards Duror in Appin, home of

their long-allies, the Stewarts.

|

| Glencoe Pass |

Aftermath

When the story reached the London press, King William said he had signed the execution order among a mass of other papers, without knowing its contents; though he had not only signed, but countersigned every document.

It was not until April 1695 that the King finally appointed a commission to investigate the affair, which concluded the orders did not authorise a massacre, and that the incident was the result of a long-standing feud between the Campbell and the MacDonald clans. Dalrymple was dismissed, and Glenlyon condemned by the commission and died in poverty at Bruge.

King William formally pardoned John MacDonald, the 13th Chief of Glencoe, who rebuilt the family home at

Carnoch while his brother, Alastair, fought in the Jacobite rebellion in 1715 alongside John Campbell, the son of Captain Campbell. The last stand of the men of Glencoe was at Culloden, after the defeat their houses were again burned and the Chief imprisoned.

The Campbells believed they were under

'The curse of Glencoe', and split into factions, one of which supported the Jacobites and the other, the Protestant Hanovarians. At the battle of Sherriffmuir in 1715, McDonalds and some Campbells fought on the same side, which tends to contradict the story of eternal enmity between the two clans.

A monument to the fallen MacDonalds lies in Glencoe village, and MacIain

was buried on the island of Eilean Munde, in Loch Leven. Generations of Scots children have been taught

‘never trust a Campbell,’ To this day the old Clachaig Inn at Glencoe carries the sign on its door,

'No Hawkers or Campbells'.

|

| Glencoe memorial |

Sources

Jimmy Powdrell Campbell

The Paisley Army

What They Don't Tell You

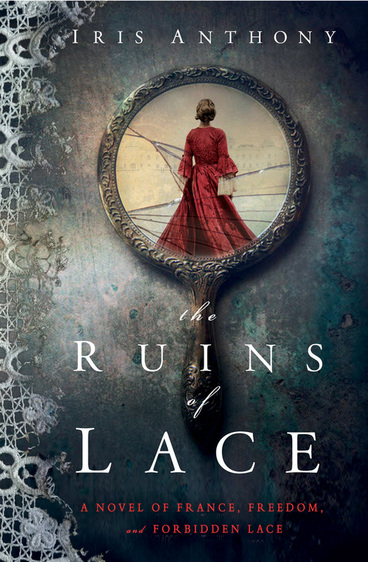

When was lace outlawed in France ... and why?

When was lace outlawed in France ... and why?