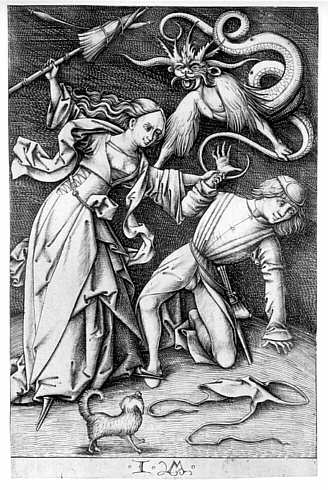

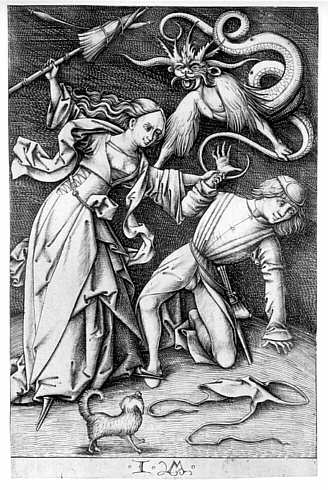

"The Evil Wife" by Israhel van Meckenem, 1440/1445-1503

A woman, encouraged by a demon, beats her husband with her distaff.

PART TWO

By the latter half of the 15th century, the feudal agrarian economy was beginning to crumble, while the capitalist market economy was growing more and more powerful, as did economic competition between men and women. Men active in the market economy tried to further their interests by simultaneously excluding women from many professions and trying to marginalize the domestic economy by claiming that home-produced goods were inferior to shop-produced goods. The guilds also began excluding women. Feeling their livelihood threatened by the competition with wealthy burghers, who set up their own industries and arranged for peasants to manufacture goods for them, male guild members struggled to initiate restrictions for women in the guilds. In 1494 in Cologne, for example, women were driven out of the harness-making guild for the first time. (Rauer 108).

In addition, traditionally "female" professions such as medicine were being taken over by men; male doctors had grown popular among the wealthy classes and were now also making inroads on medical care for the lower classes, and even encroaching on the very traditionally feminine occupation of midwifery (Ehrenreich and English 15-16--please note that the scholarship of this particular text has been called into question). Now we see the beginning of the sexual division of labor: women were beginning to be pushed into the ever-shrinking domestic economy, while men attempted to make the market economy their exclusive domain. This trend not only effected women on a purely economic level, but it also had a profound effect on women's social and sexual status. "The contraction and redefinition of women's productive and domestic roles was consistent with changes in the ideology of sexuality" (Merchant 150).

The Renaissance also ushered in a new ideal of bourgeois womanhood. The domestic sphere of the housewife and mother was idealized by Protestant intellectuals such as Martin Luther. "Gott hat Mann und Frau geschaffen, das Weib zum Mehren mit Kinder tragen; den Mann zum Naehren und Wehren," the Father of the Reformation wrote, advocating strict gender roles. "Im weltlichen politischen Regiment und Handeln antugen sie [Frauen] nichts, dazu sind Maenner geschaffen und geordnet von Gott, nicht die Weiber" (Rauer 112-113). (God created man and woman so that the woman would bear children and that the man would provide and defend. In worldly politics and trade, women should have no part--God created and ordained men for this, not women.) It must, however, be pointed out that Luther's own wife, the ex-nun Katharina von Bora was a very strong woman, beloved by her husband, who addressed her as "Herrin," or "my boss." She took charge of their household finances, farmed, raised and slaughtered livestock, and brewed vast quantities of beer to support Luther and his theology students and keep their household fed. She was the sole woman to take part in Luther's otherwise exclusively male "table talk" discussions.

Despite the positive recognition of woman as wife and mother that took place in the early Reformation, the misogynist ideology of the Catholic Church, such as Thomas Aquinas's contention that women are by nature morally weaker than men, remained in both Catholic and Protestant Churches. Also, Renaissance humanism pushed upper class women into the narrow role of being well-educated but submissive helpmates to their scholarly husbands. In 1499, Konrad Reutinger extolled his wife as the perfect Renaissance woman:

habe ich als Gattin ein Maedchen heimgefuehrt . . . schamhaft, bescheiden, schoen, etwas erfahren in den lateinischen Wissenschaften, die nie von ihren Hausgenossen streit- order schmaehsuechtig gesehen worden ist . . . . Daher weiss ich dem besten und groessten Gott jetzt und in Zukunft Dank, der meinem Studium eine Gefaehrtin und Anhaengerin gegeben hat, die mir aufs innigste vertraut ist. (Ibid 133)

(

I've taken a girl home to be my wife [who is] modest, docile, beautiful, with some knowledge of Latin that those in her household have never come to view as overly ambitious or aggressive . . . . For this I thank the best and greatest God now and always, that he has given me for my studies a companion and follower in whom I trust absolutely.)

The Renaissance also saw the birth of a brand new bourgeois motherhood ideal. In the Middle Ages, mothers were expected to take care of their young children, but the mother-child bond was not as glorified to an almost sacred institution and be-all and end-all of a woman's existence as it would become in later centuries. Also, childhood, as we now view it, did not exist then; children were treated as small adults. Children of the lower classes who survived infant hunger and childhood diseases were sent away from their parents as soon as they were old enough to find work as servants in the wealthier estates (Hoher 20).

In the second half of the 15th century, the Catholic Church was losing its authority, under threat by serious challenges and dissent that would soon take the shape of the Reformation. During this divisive time, the Catholic Church expressed a new kind of religious aggression in enforcing morality and a new fascination with the devil. The hedonism that had reigned in medieval plebeian culture was no longer to be benignly overlooked. Wifely obedience in marriage began to be emphasized more and more. During this period, a new genre of literature originated: the Devil Book, which concentrated on explaining how certain activities, such as dancing and drinking, were sinful. The general effect of these publications was to imply that the devil was everywhere (Midelfort 69). The Catholic Church's attitude towards witchcraft also changed quite significantly--the ancient code saying it was sinful to believe in witches was reversed; now Church officials declared it sinful

not to believe in them. They argued that a new sect had developed, which even the Fathers of the Church had been unable to foresee (Chamberlin 137). In 1484, Pope Innocent and two German Dominican friars, Kramer and Sprenger, issued a bull against witchcraft in response to rumors of widespread witch activity in Germany. This bull granted the use of inquisitorial techniques in witch hunting. Although the late 15th century was noted for religious intolerance, it was also characterized by a "new carelessness in law" (Ibid 69). The use of torture was revived with the re-establishment of Roman Law. This resulted in a considerable escalation in witch persecutions: "Torture allowed accusations to proliferate to epidemic proportions, because once a witch confessed under torture, she would be tortured again to divulge the names of her neighbors seen at the Sabbat" (Ruether 102). In 1486, Kramer and Sprenger's

Malleus Maleficarum was published. This highly misogynistic witch-hunting manual established the belief that women are by nature more prone to witchcraft than men: "

Femina comes from

Fe [faith] and

Minus, since she is ever weaker to hold the faith . . . . Therefore, a wicked woman is by her nature quicker to waver in her faith, and consequently quicker to abjure the faith, which is the root of witchcraft" (Malleus 44). The authors of the book were also obsessed with the idea that the unquenchable carnal lust of women drove them to the devil: "All witchcraft comes from carnal lust, which in women is insatiable . . . . Wherefore for the sake of fulfilling their lusts they consort with devils . . . it is sufficiently clear that it is no matter for wonder that there are more women than men infected with the heresy of witchcraft (Ibid 43).

As we have seen, women were beginning to be perceived as a threat to the new economic and religious developments. One cannot imagine that they were at all cooperative with the new infringements on the relative economic and sexual freedom they had enjoyed in the past. They would not submit easily to these changes--they would resist--and their resistance would make them a threat to the interests of the new order. In the arts and media of this period, women were constantly portrayed as domineering, threatening, lustful, violent, and powerful: a force that must be quelled. Village festivals of this period often had floats featuring wives beating their husbands, hurling refuse and rocks at them, and verbally abusing them. Numerous art works of this era, especially the works of Hans Baldung Grien and Albrecht Duerer, depicted the supposed disorder wrought by lusty women. Popular illustrations portrayed women beating their husbands with distaffs. Spinning was one of the occupations with which a woman could still make a decent living. The distaff symbolized her earning power and economic independence from her husband. These male artists interpreted woman's breadwinning power as something threatening, something she abused: her pride of being able to earn undermined her husband's authority. These women were not conforming to the new mold of wifely obedience that Church officials were stressing more and more. Thus, not only were women a threat to their husband's authority, they were also a threat to society in general.

One 1521 engraving by Urs Graf (unfortunately I could not find a jpeg of it to post here) depicts two young women savagely beating a monk who has probably molested them. In the Renaissance, women were portrayed as capable of violence, revenge, and self-defense. Urs Graf's women respect neither male nor religious authority; they assume the right to punish any man who tries to molest them. Hans Baldung Grien's engraving, "Aristotle and Phyllis," below, shows the legendary Phyllis literally making an ass of Aristotle. In all these pictures, women are portrayed as violent, crafty, and insubordinate. Their male victims are portrayed as pathetic, weak-willed fools for allowing themselves to be dominated by women. The message that I read into these art works is that women are trying to hold the upper hand. They will not allow themselves to be forced into the new "proper" feminine sphere. In order for women to be put in their place, men must assert their dominance. Thus, these male artists perceive women as a powerful, chaotic force that needed to be violently subdued. This violence against women would not be long in coming.

"Hercules among the maids of Queen Omphale" by Lucus Cranach the Elder: these women are emasculating the mighty Hercules by dressing him in a women's coif and pressing a distaff into his hand.