.jpg) Among

the (possibly) inappropriate reading I indulged in as a young teenager (where was Harry

Potter?), I devoured the stories of Robert Neill, who wrote several books set

in the English Civil War period. His book “Witch

Bane” begins with a young woman suspected of witchcraft being publicly stripped

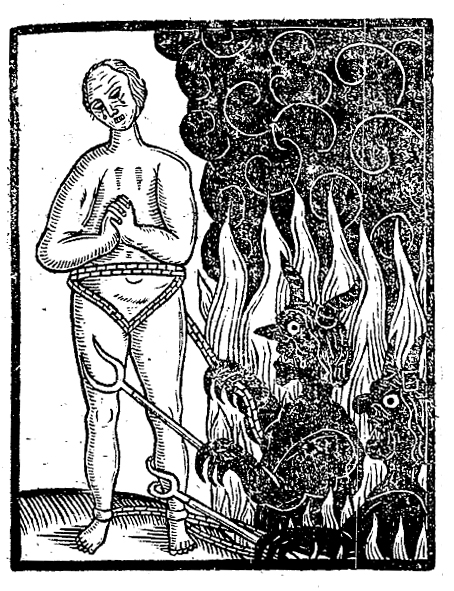

and submitted to trial by “pricking”. (It was a common belief held that a witch

could be discovered through the process of pricking their skin with needles,

pins and bodkins and body of the woman (or man!) was closely searched for the “witch’s

mark” to which the bodkin was applied in the belief that the person would not

feel pain or bleed when pricked). Even though “Witch Bane” is long out of

print, I won’t give away any more of the plot but the slightly salacious cover

alone was enough to grip me from the start!

Among

the (possibly) inappropriate reading I indulged in as a young teenager (where was Harry

Potter?), I devoured the stories of Robert Neill, who wrote several books set

in the English Civil War period. His book “Witch

Bane” begins with a young woman suspected of witchcraft being publicly stripped

and submitted to trial by “pricking”. (It was a common belief held that a witch

could be discovered through the process of pricking their skin with needles,

pins and bodkins and body of the woman (or man!) was closely searched for the “witch’s

mark” to which the bodkin was applied in the belief that the person would not

feel pain or bleed when pricked). Even though “Witch Bane” is long out of

print, I won’t give away any more of the plot but the slightly salacious cover

alone was enough to grip me from the start!

So

as Halloween approaches and thoughts turn to “ghosties

and ghoulies and long legged beasties and things that go bump in the night”, I

cast around for an appropriate topic for this post. There are others who are experts in the area of seventeenth century witches but,

in the memory of “Witch Bane”, I thought I might have a look at one person

whose name inspired fear throughout England of the 1640s and 1650s… Matthew

Hopkins - The Witchfinder General.

"Thou shalt not suffer a witch to live" EXODUS xxn. 18

In

1604 James I passed the the Witchcraft Statute which made “witchcraft”

a capital offence if the victim was injured. It also incorporated a number of

continental notions of witchcraft, including those of, a pact with, and worship

of, the devil and made the exhumation of bodies for “magical purposes” a crime.

This statute remained in force until 1736, when it was finally repealed.

Following the Lancashire witch trials of 1634, there was a requirement of

material proof of being a witch (some physical manifestion of a pact with the

devil).

Little

is known of Matthew Hopkins’ early life. It is

thought he was born in Little Wenham in Suffolk in the early 1620s (making him

a comparitively young man at the time he rose to infamy). It is postulated that

he studied law.

The

English Civil War (1642-1645) was at its height when Matthew first comes to

public notice. In a country torn apart by violence, politics and religion and

where fear and superstition prevailed, the moment was opportune for a young man

with a fervent belief that he had the power to rid the country of witches and

in 1644 we have the first public mention of Matthew. Essex and the Eastern

counties where Matthew worked was the seat of power for the puritan forces and

it is from this seething hot bed of religious fervour that the witch mania

rose.

In

1644 Hopkins fell in with an already established “witch

pricker”, John Stearne. Hopkins

claimed to have overheard several witches discussing their meetings with the

devil: “…March 1644 he had some seven or eight of that horrible sect of Witches

living in the Towne where he lived, a Towne in Essex called Maningtree, with divers

other adjacent Witches of other towns, who every six weeks in the night (being

alwayes on the Friday night) had their meeting close by his house and had their

severall solemne sacrifices there offered to the Devill, one of which this

discoverer heard speaking to her Imps one night, and bid them goe to another

Witch…”

In

1644 Hopkins fell in with an already established “witch

pricker”, John Stearne. Hopkins

claimed to have overheard several witches discussing their meetings with the

devil: “…March 1644 he had some seven or eight of that horrible sect of Witches

living in the Towne where he lived, a Towne in Essex called Maningtree, with divers

other adjacent Witches of other towns, who every six weeks in the night (being

alwayes on the Friday night) had their meeting close by his house and had their

severall solemne sacrifices there offered to the Devill, one of which this

discoverer heard speaking to her Imps one night, and bid them goe to another

Witch…”

As

a consequence a trial of twenty three women was held at Chelmsford in 1645.

Four died in prison and nineteen were hung. Following the notoriety of that

trial Hopkins and Stearne became self appointed “witch

finders” (the term Witch Finder General bears no official stamp of approval).

The work of carrying out the “pricking” was done by well paid (and no doubt

zealous) female assistants. In the vacuum of proper authority caused by the war,

Hopkins and Stearne operated throughout the eastern counties with relative impunity.

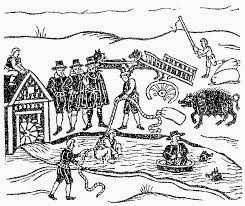

.jpg) Hopkins’

favourite methods of interrogation (bearing in mind torture was by now illegal

in England) were “swimming” (where the woman was bound and thrown into a pond…if

she floated she was deemed a witch as she was being rejected the waters of baptism…if

she sank, and most likely drowned, then obviously she was innocent); cutting

with a blunt knife or sleep deprivation. Hopkins was ordered to discontinue

swimming in 1645, unless he had the subject’s permission! By far his favourite

was “pricking” (described briefly above). The victim would be shaved of all

hair and if a mole or an extra nipple was discovered, it was deemed that this

would be the means by which the witch would suckle the devil or an incubus or

imp. If found guilty the most common form of execution was hanging. It is

estimated that Hopkins was probably responsible for the death of some 200

people between 1645 and 1647.

Hopkins’

favourite methods of interrogation (bearing in mind torture was by now illegal

in England) were “swimming” (where the woman was bound and thrown into a pond…if

she floated she was deemed a witch as she was being rejected the waters of baptism…if

she sank, and most likely drowned, then obviously she was innocent); cutting

with a blunt knife or sleep deprivation. Hopkins was ordered to discontinue

swimming in 1645, unless he had the subject’s permission! By far his favourite

was “pricking” (described briefly above). The victim would be shaved of all

hair and if a mole or an extra nipple was discovered, it was deemed that this

would be the means by which the witch would suckle the devil or an incubus or

imp. If found guilty the most common form of execution was hanging. It is

estimated that Hopkins was probably responsible for the death of some 200

people between 1645 and 1647.

He

wrote a pamphlet describing his methods - The Discovery of Witches - which made

its way across the Atlantic to the new colonies and his methods were employed

in the witch trials of the New World, most notably the Salem witch trial of the

1690s.

However by 1647 Hopkins began to run into opposition. Sermons were preached

against the work of Hopkins and Stearne and his methods (and the fees he

charged for his work) were called into question by the authorities in Norfolk.

|

| Mistley Pond |

Matthew

Hopkins died in August 1647 in his home town of Manningtee in Essex. While it

is more than likely that nothing more extraordinary than tuberculosis carried

him off, for such a controversial figure there is a legend that he met his end

after being accused of witchcraft and subjected to his own ‘swimming’

test. It is said his ghost haunts the pond at Mistley.

The last execution in England for witchcraft

was Alicia Molland who was executed in Essex in March 1684,he last conviction

in 1712

And in the spirit of Halloween here is the master of horror himself, Vincent Price, in his 1968 portrayal of Matthew Hopkins in the film "The Witchfinder General".

Sweet dreams...