In the spirit of Halloween, I though I'd continue my blogs about little known witch trials. New Hampshire had a few trials in Hampton when the colony was considered part of Massachussetts. Jane Walford's troubles seem to have begun in 1648. She spent many years fighting accusations of being a witch. Supposedly she appeared to a couple of neighbors in the form of a cat, and other neighbors said they could not speak when she appeared to them. She was allowed to go on good behavior. On more than one occasion, Jane successfully sued her neighbors for slander.

In 1680, Jane's daughter was accused of being a witch, but she was not convicted.

Eunice Cole was accused during the same time frame as Jane. For over twenty years neighbors of Hampton gossiped that Eunice was of a terrible character, and she was feared for being in "Alliance with the Devil." Two young men drowned in the Hampton River, and Eunice was believed to have been the cause. A couple of neighbors said Eunice had caused the death of a couple of calves. She was also believed to have made unearthly scratching noises on neighbors' windows. Eunice was whipped and spent fifteen years in and out of jail.

Shortly after her release, she was again arrested for being a witch. She was found not guilty of witchcraft, but there was enough suspicion to believe that she had familiarity with the devil. She died soon after in poverty. In 1938, she was acquitted, and her full citizenship of the town was restored.

Also, from Hampton was Rachel Fuller. She was accused of using witchcraft on a neighbor's child. Ironically, the neighbor in question, John Godfrey had been tried as a witch in Massachusetts three times himself long before the Salem trials. Rachel used herbs, rubbed them in her hands, and threw them around the hearth. Afterward, she announced the child would be well. When the child died, she went through a formal hearing

Isabelle Towle was also jailed for being a witch, but nothing further can be found on her.

In 1683, the only witch trial in Pennsylvania was that of Margaret Mattson and Yeshro Henrickson. Margaret was supposedly a healer in Finnish tradition. Several neighbors claimed that she had bewitched their cows and geese. She also appeared to witnesses in the form of an old woman with a knife in green light. Another old woman Yeshro Hendrickson was also accused, but her name seems to vanish from the record. Margaret couldn't speak English and an interpreter was needed for the trial. She was found guilty for having a reputation of being a witch, but not bewitching the cattle.

Kim Murphy

www.KimMurphy.net

Pages

▼

Sunday, 28 October 2012

Sunday, 21 October 2012

Henry Stuart, Prince Of Wales

I have slipped backwards Century wise with this post, but found this character particularly fascinating.

Born at Stirling Castle in February 1594, as Duke of Rothesay, Earl of Carrick, Baron of Renfrew, Lord of The Isles and Prince and Great Steward of Scotland. Henry Frederick was named after his murdered grandfather, Henry Darnley, the second husband of Mary Queen of Scots, and Frederick II of Denmark.

James I was concerned [or paranoid] that his wife’s interest in Catholicism would influence their son, so he placed him in the care of Alexander Erskine, Earl of Mar with whom Henry stayed for the first eight years of his life. James was equally protective of his other two children, Elizabeth who became Queen of Bohemia and Charles I, who were also removed from their mother’s care at a young age. Elizabeth was born at Falkland Palace, Fife and brought up at Linlithgow Palace. Her father became King when she was six, and Elizabeth came to England under her governess the Countess of Kildare, but was later consigned to the care of Lord Harington and grew up at Combe Abbey in Warwickshire.

Charles was born in Dunfermline Palace, but was not considered strong enough to make the journey to London when his parents and older siblings left for England. He was only reunited with his family when he was three and a half and could walk the hall at Dunfirmline unaided.

entered Magdalen College, Oxford, where the hugely popular young man became interested in sports. His other interests included naval and military affairs, and national issues, about which he often disagreed with his father. He also disapproved of the way James I conducted the royal court, disliked his favourite, Robert Carr and was friends with Sir Walter Raleigh and campaigned for him to be released from the Tower of London.

In 1610, Henry was invested as Prince of Wales, by which time his popularity eclipsed his father, causing tension between them. On one occasion they were hunting near Royston when James I criticized his son for lacking enthusiasm for the chase. Henry moved to strike his father with a caneollowed by most of the hunting party.

Henry is said to have disliked his younger brother, Charles, and once teased him by snatching off the hat of a bishop and put it on the younger child's head, saying he would make Charles Archbishop of Canterbury when he was king, so Charles would have a long robe to hide his ugly, rickety legs. Charles was only nine and had to be dragged off in tears after stamping on the cap.

Henry was ardently Protestant and fiercely moral as well as being an enthusiastic patron of the arts. He collected paintings, sculpture and books, enjoyed music and literature, and commissioned garden designs and architecture, as well as personally performing in court festivities and masques. He took an active interest in the navy and sponsored an expedition to find the North-West Passage, subsequently giving his name to new settlements in Virginia.

When the king proposed a French marriage for Henry, he answered that he was 'resolved that two religions should not lie in his bed.' He was also approving of his sister Elizabeth's proposed match to the Protestant Frederick, Elector Palatine.

At the age of 16 he was already building up a spectacular art collection, including Holbein drawings [now held in the Windsor Castle library]. He was also so interested in shipbuilding that Sir Walter Raleigh, imprisoned in the tower, wrote him a treatise on the subject.

'Upright to the point of priggishness, he fined all who swore in his presence', according to Charles Carlton, a biographer of Charles I, who describes Henry as an 'obdurate Protestant'. who ensured his household attended church services, and himself listened humbly, attentively and regularly to the sermons preached to his household.

In November 1612, just before his nineteenth birthday, Henry contracted typhoid fever. While on his deathbed, the 12-year-old Charles sent for the horse and gave it to his brother hoping it would cheer him up - but it was too late, Henry died.

Prince Henry's death was widely regarded as a tragedy for the nation. According to Charles Carlton, 'Few heirs to the English throne have been as widely and deeply mourned as Prince Henry.' His body lay in state at St James Palace for four weeks, and over a thousand people walked in the mile-long cortege to Westminster Abbey to hear the two-hour sermon delivered by the Archbishop of Canterbury. As Henry's body was lowered into the ground, his chief servants broke their staves of office at the grave.

A contemporary record notes: “There was to bee seene an innumerable multitude of all sorts of ages and degrees of men, women and children... some weeping, crying, howling, wringing of their hands, others halfe dead, sounding, sighing inwardly, others holding up their hands, passionately bewayling so great a losse, with Rivers, nay with an Ocean of teares.”

Charles was the chief mourner at Henry's funeral, which James I (detesting funerals) refused to attend. All of Henry's automatic titles passed to Charles. Months later, in the middle of a conversation with diplomats, the king suddenly collapsed, sobbing: "Henry is dead, Henry is dead."

The National Portrait Gallery in Trafalgar square is holding an exhibition entitled: The Lost Prince: The Life and Death of Henry Stuart which runs from October 18 2012 - January 13 2013.

Born at Stirling Castle in February 1594, as Duke of Rothesay, Earl of Carrick, Baron of Renfrew, Lord of The Isles and Prince and Great Steward of Scotland. Henry Frederick was named after his murdered grandfather, Henry Darnley, the second husband of Mary Queen of Scots, and Frederick II of Denmark.

James I was concerned [or paranoid] that his wife’s interest in Catholicism would influence their son, so he placed him in the care of Alexander Erskine, Earl of Mar with whom Henry stayed for the first eight years of his life. James was equally protective of his other two children, Elizabeth who became Queen of Bohemia and Charles I, who were also removed from their mother’s care at a young age. Elizabeth was born at Falkland Palace, Fife and brought up at Linlithgow Palace. Her father became King when she was six, and Elizabeth came to England under her governess the Countess of Kildare, but was later consigned to the care of Lord Harington and grew up at Combe Abbey in Warwickshire.

|

| Charles Stuart Circa 1615 |

Charles was born in Dunfermline Palace, but was not considered strong enough to make the journey to London when his parents and older siblings left for England. He was only reunited with his family when he was three and a half and could walk the hall at Dunfirmline unaided.

At his father's accession in 1605, Henry became Duke of Cornwall and

|

| Henry Stuart on Horseback |

In 1610, Henry was invested as Prince of Wales, by which time his popularity eclipsed his father, causing tension between them. On one occasion they were hunting near Royston when James I criticized his son for lacking enthusiasm for the chase. Henry moved to strike his father with a caneollowed by most of the hunting party.

Henry is said to have disliked his younger brother, Charles, and once teased him by snatching off the hat of a bishop and put it on the younger child's head, saying he would make Charles Archbishop of Canterbury when he was king, so Charles would have a long robe to hide his ugly, rickety legs. Charles was only nine and had to be dragged off in tears after stamping on the cap.

|

| Elizabeth Stuart |

When the king proposed a French marriage for Henry, he answered that he was 'resolved that two religions should not lie in his bed.' He was also approving of his sister Elizabeth's proposed match to the Protestant Frederick, Elector Palatine.

At the age of 16 he was already building up a spectacular art collection, including Holbein drawings [now held in the Windsor Castle library]. He was also so interested in shipbuilding that Sir Walter Raleigh, imprisoned in the tower, wrote him a treatise on the subject.

'Upright to the point of priggishness, he fined all who swore in his presence', according to Charles Carlton, a biographer of Charles I, who describes Henry as an 'obdurate Protestant'. who ensured his household attended church services, and himself listened humbly, attentively and regularly to the sermons preached to his household.

In November 1612, just before his nineteenth birthday, Henry contracted typhoid fever. While on his deathbed, the 12-year-old Charles sent for the horse and gave it to his brother hoping it would cheer him up - but it was too late, Henry died.

Prince Henry's death was widely regarded as a tragedy for the nation. According to Charles Carlton, 'Few heirs to the English throne have been as widely and deeply mourned as Prince Henry.' His body lay in state at St James Palace for four weeks, and over a thousand people walked in the mile-long cortege to Westminster Abbey to hear the two-hour sermon delivered by the Archbishop of Canterbury. As Henry's body was lowered into the ground, his chief servants broke their staves of office at the grave.

|

| Anne of Denmark in Mouring |

Charles was the chief mourner at Henry's funeral, which James I (detesting funerals) refused to attend. All of Henry's automatic titles passed to Charles. Months later, in the middle of a conversation with diplomats, the king suddenly collapsed, sobbing: "Henry is dead, Henry is dead."

The National Portrait Gallery in Trafalgar square is holding an exhibition entitled: The Lost Prince: The Life and Death of Henry Stuart which runs from October 18 2012 - January 13 2013.

Anita Davison

Saturday, 13 October 2012

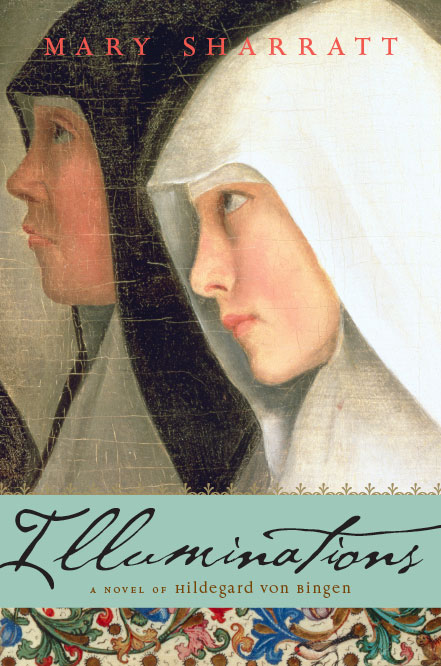

Hildegard von Bingen: Green Saint and Timeless Visionary

Video trailer of my new novel, Illuminations: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen.

Hildegard von Bingen (1098–1179) was a visionary abbess and polymath. She composed an entire corpus of sacred music and wrote nine books on subjects as diverse as theology, cosmology, botany, medicine, linguistics, and human sexuality, a prodigious intellectual outpouring that was unprecedented for a 12th-century woman. Her prophecies earned her the title Sybil of the Rhine.

Pope Benedict XVI canonized Hildegard on May 10, 2012—873 years after her death. On October 7, 2012, she was elevated to Doctor of the Church, a rare and solemn title reserved for theologians who have significantly impacted Church doctrine.

But what does Hildegard mean for a wider secular audience today?

I believe her legacy remains hugely important for contemporary women.

While writing Illuminations: A Novel of Hildegard von Bingen, I kept coming up against the injustice of how women, who are often more devout than men, are condemned to stand at the margins of established religion, even in the 21st century. Women bishops still cause controversy in the Episcopalian Church while the previous Catholic pope, John Paul II, called a moratorium even on the discussion of women priests. Although Pope Benedict XVI is elevating Hildegard to Doctor of the Church, he is suppressing Hildegard’s contemporaries, the sisters and nuns of the Leadership Council of Women Religious, who stand accused of radical feminism.

Modern women have the choice to wash their hands of organized religion altogether. But Hildegard didn’t even get to choose whether to enter monastic life—aacording to Guibert of Gembloux's Vita Sanctae Hildegardis, she was entombed in an anchorage at the age of eight. The Church of her day could not have been more patriarchal and repressive to women. Yet her visions moved her to create a faith that was immanent and life-affirming, one that can inspire us today.

Too often both religion and spirituality have been interpreted by and for men, but when women reveal their spiritual truths, a whole other landscape emerges, one we haven’t seen enough of. Hildegard opens the door to a luminous new world.

The cornerstone of Hildegard’s spirituality was Viriditas, or greening power, her revelation of the animating life force manifest in the natural world that infuses all creation with moisture and vitality. To her, the divine is manifest in every leaf and blade of grass. Just as a ray of sunlight is the sun, Hildegard believed that a flower or a stone is God, though not the whole of God. Creation reveals the face of the invisible creator.

“I, the fiery life of divine essence, am aflame beyond the beauty of the meadows,” the voice of God reveals in Hildegard’s visions, recorded in her book, Liber Divinorum. “I gleam in the waters, and I burn in the sun, moon and stars . . . . I awaken everything to life.”

Hildegard’s re-visioning of religion celebrated women and nature, and even perceived God as feminine, as Mother. Her vision of the universe was an egg in the womb of God.

According to Barbara Newman’s book Sister of Wisdom: St. Hildegard’s Theology of the Feminine, Hildegard’s Sapientia, or Divine Wisdom, creates the cosmos by existing within it.

O power of wisdom!

You encompassed the cosmos,

Encircling and embracing all in one living orbit

With your three wings:

One soars on high,

One distills the earth’s essence,

And the third hovers everywhere.

Hildegard von Bingen, O virtus sapientia

Hildegard shows how visionary women might transform the most male-dominated faith traditions from within.